Researchers discover how cells repair structures that contribute to longevity

/A new study describes how cells repair damaged lysosomes, which promote longevity by eliminating or recycling cellular trash.

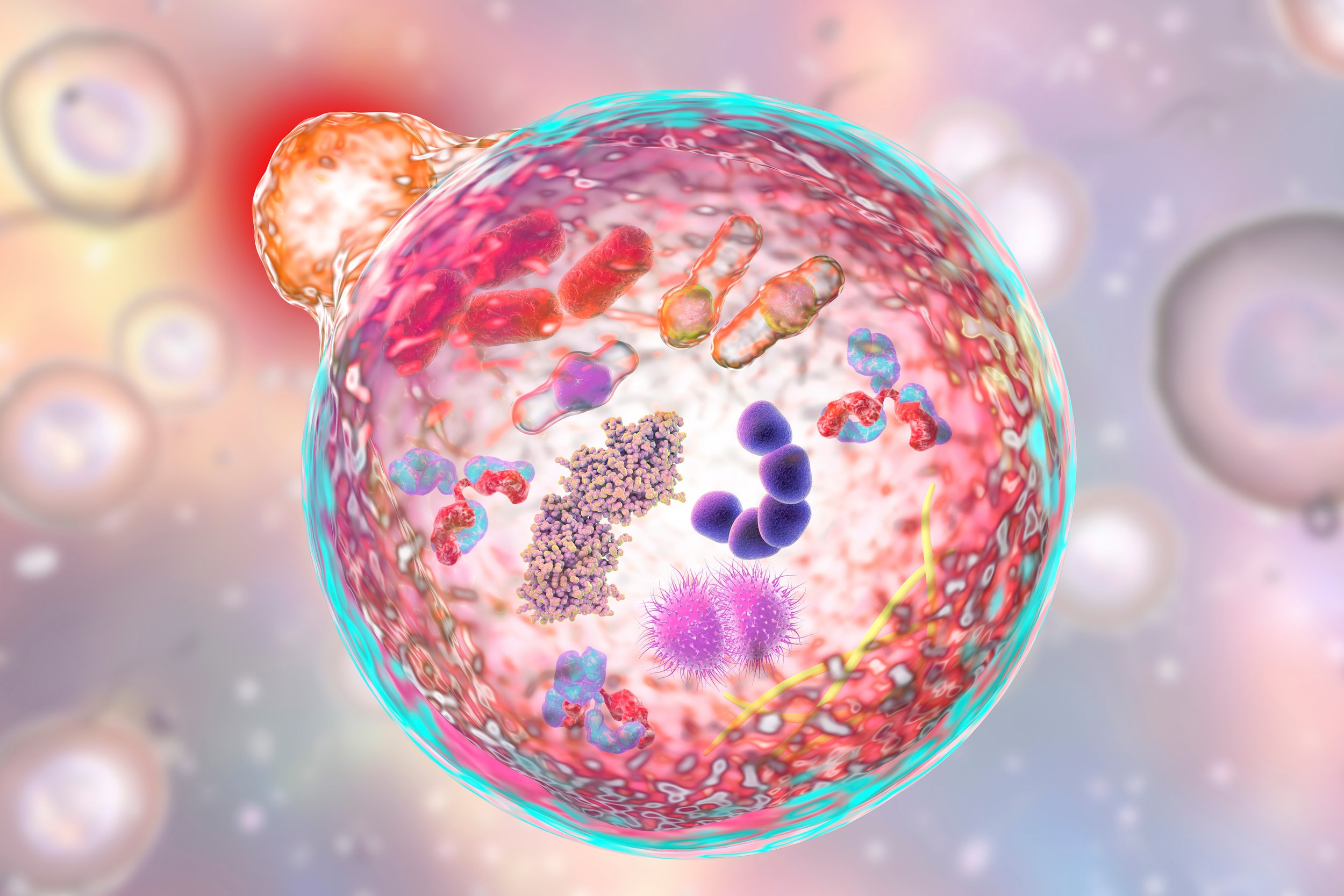

Lysosomes are organelles enclosed in a membrane within cells. These organelles contain enzymes that can break down all types of biological polymers, including proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates and lipids.

For years, we have known that lysosomes serve as the cells’ digestive systems, degrading junk picked up from outside the cell and digesting obsolete cell components. We also know that lysosomes often get injured as they age. Lysosome injury, a hallmark of aging, can result in a variety of progressive diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders.

Now a study by University of Pittsburgh scientists, published in the journal “Nature,” has found how cells repair lysosomal damage.

An enzyme called PI4K2A accumulates on lysosomes within minutes of their being damaged, and it generates high levels of a signaling molecule called PtdIns4P. The molecule attracts oxysterol-binding protein-related (ORP) proteins, that link the PtdIns4P on the lysosome to the endoplasmic reticulum, the cellular structure involved in the synthesis of proteins and lipids. This reticulum wraps around the lysosome, shuttling cholesterol and a lipid called phosphatidylserine to the lysosome, which help to patch holes in the membrane that encloses the lysosome.

Researchers who identified these steps in lysosomal repair have named it the PITT -- phosphoinositide-initiated membrane tethering and lipid transport-- Pathway.

They conclude that in healthy people, small breaks in the lysosome membrane are quickly repaired. But, if the damage is too extensive or the repair pathway is compromised by age or disease, leaky lysosomes accumulate, potentially causing other problems.

For example, in Alzheimer’s, leakage of tau fibrils from damaged lysosomes is linked to the disease’s progression. When Pittsburgh researchers deleted the gene encoding of the first enzyme in the pathway, PI4K2A, they found that tau fibril spreading increased significantly, suggesting that defects in the PITT pathway could contribute to Alzheimer’s disease progression.

It’s not clear how important membrane damage is to lysosomal decline in later life. Another issue involves the buildup of cell waste that the lysosome cannot break down, a situation that takes place with inherited lysosomal storage conditions. In the elderly, this can lead to cell dysfunction or death.

But the research is fascinating because it demonstrates the importance of cellular maintenance. The work falls under our strategy, “Get the crud out,” which recognizes the importance of clearing harmful substances from the body at both the cellular and organ level. Destroying ineffective or harmful cells, as well as removing toxic proteins and metabolites, is essential to restoring youthful health.

“Get the crud out” is one of the seven strategies that guide Foundation investments, planning and policies.

We came up with our seven strategies because there is no single solution that will lengthen the healthy human lifespan. It will take a combination of things to help us reach our goal of making 90 the new 50 by 2030.

Join us to bring this dream to life. Donate to Methuselah Foundation.